Mr. Ovidiu Genaru, thank you for welcoming me into your creative space, this intimate universe where so many of your works were born. Our conversation revives an idea I’ve held since the pandemic: the desire to recover fragments of local history that official archives often overlook. I invite you, therefore, to what I call a “Therapy with and about Memories”—memories of Bacău as it once was, whether in the interwar or postwar period, and memories of the defining moments in Romania’s history that you personally witnessed. We also hope to explore the deeper meanings of history, which, I believe, reveal themselves only in connection with Truth and Human Virtues.

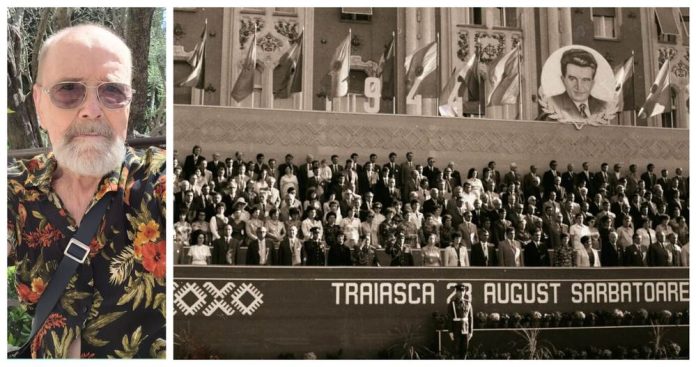

You were born in Bacău on November 10, 1934, in a Romania that was still a monarchy, yet already moving toward authoritarianism, dictatorship, and eventually totalitarianism. A quick internet search shows that the only historical event of note on that date in Romania is… your own birth: the birth of the poet, writer, and prose author Ovidiu Bibire-Genaru.

Ovidiu Genaru: Really? I had no idea! (laughs) This introduction is a bit intimidating because it’s so grand in scale. I must calibrate my memories to a much smaller scale—down to the room we’re sitting in now. After all, grand history is nothing but the sum of smaller histories, whether personal or communal. They are just as important, and often more enduring than grand history. The past is always shifting, unpredictable, and we are, in the end, the sum of our own memories.

– You lived through many pivotal moments in 20th-century Romania. Since we are approaching the anniversary of the day Romania “switched sides” in World War II, what do you remember about August 23, 1944?

– I was ten years old at the time… you realize it’s been 81 years since those events that reshaped Romania’s history. Yes, I remember that period vividly. The Russians had their front in northern Moldavia, where they paused for a while, but after August 20, the front was broken. Panic swept through our street… all the families were preparing to flee, and we did the same. We decided to head to Bucharest to escape the Russians. That night, my mother, my older brother, and I packed a few essentials into blankets and rugs, hid the most valuable things in the cellar, spoke with a local cart driver named Modrângă, and set out for the train station. There were crowds everywhere, total panic—people screaming, chaos all around. A livestock train was waiting, and we boarded it, leaving for Bucharest.

Near Râmnicu Sărat, the train stopped when the locomotive caught fire, and we got out into a field near a cornfield. The last wagon was a tanker guarded by a German soldier. That evening, the soldier bid farewell and departed westward… probably informed that Russian divisions were approaching.

I still vividly recall the German planes—probably Junkers Ju 88 or 87—bombing Russian tanks advancing on the road. I can still see the smoke rising from tanks hit by bombs from dive-bombing aircraft.

A miracle happened that night: we met my father, who had been stationed behind the front. We didn’t know where he was, and suddenly he appeared near the train. From there, we left with other families toward a military canton the next morning. Along the way, I saw Russian soldiers advancing through the cornfields toward Râmnicu Sărat. For a few hours, I was right on the front line… We were threatened with automatic weapons, forced to lie on the ground, and ordered to hand over our watches, rings, and earrings. Yes, it’s true. These are not stories… “From the Dniester to the Don: give the watch, give the coat.”

That evening, the area was completely occupied by the Red Army. I remember that near where we were—about four or five kilometers away, along a dead-end track—there was a supply train for the officers’ mess, abandoned by the German troops. It contained millions of cigarettes and all kinds of drinks from around the world, barrels full of red wine that we could help ourselves to. From there, we took cigarettes and yeast, which we exchanged for flour through small agreements with local residents—we practiced bartering. For almost two weeks, while we stayed at that canton, we ate only what we could find along the railway: corn, polenta, or, more rarely, bread.

We returned to Bacău after a long journey, with many stops, on an open freight train used for transporting planks and timber… We braved the rain, dozed wherever we could, saw numerous burned-out stations, and eventually made it back to our home on Ardealului Street. Only the lightbulbs had been stolen; everything else, our meager possessions, remained intact in a city occupied by the Russians.

– What was Bacău like during your childhood?

– My childhood Bacău was a simple market town, a commune full of “mud and corn stalks,” a “Jewish market full of huts,” as Bacovia said. My earliest memories are of the kindergarten on Banca Națională Street. I remember my teacher, Mrs. Grebenea; the great novelist George Bălăiță, my classmate in both kindergarten and high school; my years at Primary School No. 2 (today Al. I. Cuza); the special atmosphere during religious and national holidays; St. George’s Day; the willow branches at the gates; Santa Claus; the moment when part of the Ferdinand High School Library was burned by the communists; and Valea lui Ifrim, our favorite little sledding hill…

I am a man of the neighborhood, having grown up in a modest house on Ardealului Street, as it is still called today, in a family with limited financial means, working hard to pay rent and put bread on the table.

– The events of August 23, 1944, marked a profound change in Romanian society. In less than four years, virtually every aspect of Romania’s political, economic, constitutional, and cultural landscape had transformed. Your adolescence coincided with the Stalinization of our country. Were you aware of these deep changes? Did they affect your life in any way?

– Yes, of course, we felt it. Our family was persecuted. My older brother read a magazine called Signal, beautifully illustrated, published by the Germans. It was a political propaganda magazine, warning that the Stalinist kolkhoz system would bring famine—which indeed happened between 1947 and 1949. After the war, we encountered the new order: I worked at the poor people’s canteen for a bowl of pea soup, everything was rationed, while our trains departed east loaded with the earth’s wealth. A friend who recently returned from the CIS told me that the Russians still have stockpiles of the timber they took from us, stored in lakes… For today’s generations, the poverty of that time is unimaginable, and the abundance we see now is unprecedented in Romanian history—but it is built on debt. Returning to my own experience: yes, we suffered. My brother was imprisoned. I did not have a good record; I wasn’t a party member. But no one forbade me from writing, from playing sports, from having friends…

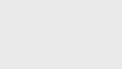

– After 1948, for 41 years, August 23 became Romania’s National Day. Initially, it celebrated “the liberation of Romania by the glorious Soviet Army.” Gradually, the original meaning was lost: the “anti-fascist armed insurrection” became the “national and social liberation revolution, anti-fascist and anti-imperialist,” and the August 23 holiday was co-opted by the communists to mark “the progress of communism” and to honor the “beloved leaders.” Attendance was almost compulsory. Did you ever find anything sincere or authentic in these orchestrated celebrations?

– It is said that at the first anniversary of August 23, in 1945, the main portraits on display were those of King Michael I, the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, American President Harry Truman, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The following year, the two Anglo-American leaders disappeared from the display, and by 1948 even King Michael was gone. I, of course, took part in organizing these demonstrations. I participated with my high school gymnastics team, climbing onto trucks… I remember the floats, the patriotic guards, and the workers called to march through the city center. We would gather near the park, marching in place for a while, then practicing the parade step. The events in our city were meager. Everything was for show. No, there was nothing sincere in this pageantry—no one truly believed in it. On the contrary, I heard many people cursing… (laughs). But you had to be there; otherwise… it wasn’t acceptable.

– Still, it must be said that after 1950, Bacău underwent a profound transformation, reaching unprecedented levels of population growth and cultural and economic development. You witnessed the city’s transition from the “Jewish market town” to the heavily industrialized city of the 1970s and ’80s.

– Yes, indeed, Bacău developed enormously during that period. Almost every economic and industrial sector was present in the cities of Bacău, Onești, and Comănești: aviation, industrial valves, petroleum extraction and processing, wood processing, the textile industry, poultry farming, Letea, and more. It seems incredible, but it was true. At one point, we were the leading economic power in Moldova and the sixth nationwide… a county rich in natural resources. Then… it was all plundered…

– We live in an age of post-truth, an era in which humanity externalizes its own historical memory onto digital media. How do you perceive the way younger generations relate to the idea of homeland, historical culture, and national celebration? Have we come to live and fight only for ourselves, selfishly, or do we still find reasons for cohesion?

– These devices—if we forget them at home, we feel lost; I mean our phones—have changed part of the world… nothing is the same. Direct human contact has been replaced by virtual forms of information transmission… a text message, an email… and this profoundly affects our ability to communicate, to socialize. They are said to be made for communication, but it is false communication. It is communication without emotion, without the joy of looking at another person… The reality we live in is no longer communal, no longer social; there is no longer a sense of togetherness. The changes are so profound that they alter our very human essence… but they didn’t happen suddenly… they were carefully planned, calculated. It is very possible that these concepts you mentioned may no longer hold any meaning for the next generation. It is already happening… We are forced to preserve our own identity, culture, and spirituality. No nation can survive, can endure, outside of its culture, outside of its own historical memory.

– Mr. Ovidiu Genaru, thank you for your time and for sharing these precious memories. They are all the more valuable for their uniqueness within the landscape of local historiography.

Alin Sebastian Popa,

Manager of the “Iulian Antonescu” Museum Complex