It was Friday, 22 December 1989. The frost bit into people’s cheeks, yet the sky over Bacău was strangely clear. Above the city hung an unusual rainbow, in pale pastel colours, like a luminous wound cut across the winter sky. “This can’t be good…,” Elena Țintaru thought, quickening her steps toward the newsroom. She did not yet know that within a few hours nothing would ever be “the same as before”.

Around 10 a.m., the newsroom of Steagul Roșu appeared to be functioning according to its familiar routine. The weekly edition had been written and prepared for print. Eugen Verman and Elena Țintaru were proofreading, while the other editors were glued to the television in editor-in-chief Petru Filioreanu’s office, watching the images coming from Bucharest with clenched hearts. They could see it, they could hear it — but their minds refused to believe it: Romania was boiling.

It was known that Natalia Jipa, the propaganda secretary of the County Party Committee, was due to arrive. She was to announce “official” changes — at Ateneu and at Steagul Roșu. These were party reshuffles, still made under the old regime. No one suspected that history was about to trample all of it underfoot, right before their eyes.

Around 11 a.m., Natalia Jipa entered the newsroom. Agitated, visibly shaken. In the meeting room, she hurriedly read the documents: Petru Filioreanu was to take over Ateneu, while Steagul Roșu was to have a new editor-in-chief, Mihai Buznea. Then came a phone call. One that took everyone’s breath away. Nicolae Ceaușescu had announced that “the traitor Milea has committed suicide”.

There was a second of dense, crushing silence. “He didn’t commit suicide… he was shot,” Elena Țintaru murmured. Natalia Jipa’s eyes filled with tears. She stood up and left in haste. No one was installed. History no longer had patience for procedures.

From that moment on, the newsroom rallied around a new core: Mihai Buznea, Dumitru Mitulescu, Constantin Nancu, Eugen Verman, Ștefan Olteanu, Elena Țintaru, Petru Done, Ioan Enache, and photojournalist Constantin Bursuc. No one left. No one backed down. The decision was made: the old newspaper could no longer appear. A different one had to be created. A newspaper that would burn.

Down at the printing house, Steagul Roșu had eight pages ready. But they were communist pages, filled with praise and lifeless formulas. They were discarded without hesitation. Only two pages remained — Economy and Sports. Too little. It was 3 p.m. Time was rushing forward.

“How many pages?” Eugen Verman asked.

“Four. Only the essentials. We have to be free,” Mihai Buznea replied.

In the newsroom, no one thought about themselves, about family, about rest. Television and radio ran in parallel. The dictator had fled by helicopter. The risk was assumed. The new paper had to come out.

Then came the decisive question: what would it be called?

“Luptătorul” (The Fighter), Dumitru Mitulescu suggested. Too closely tied to the past.

“Libertatea”, “Vocea Bacăului” — names floated through the air.

Then Eugen Verman: “Deșteptarea de Bacău.”

“Why not just Deșteptarea?” Constantin Nancu said.

And so it remained. Deșteptarea. A simple word, but an explosive one.

The reporters scattered across the city. Ioan Enache went to the County Committee, Ștefan Olteanu stayed by the television, the others took the pulse of the streets. Steagul Roșu was thrown away. It would never appear again.

That evening, the newsroom filled up. Contributors arrived: Vasile Pruteanu, Constantin Călin, Iacob Florea, Doru Kalmuschi, Florin Filioreanu. Two young aspirants appeared as well: Răzvan Haritonovici and Sandor Boros. Everyone signed the first issue. Coffee came from neighbours, food from friends. One phone rang from time to time, just to reassure families: “I’m not coming home. We’re putting out the paper.”

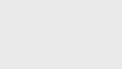

From the printing house came the proofs, the ink still wet. The headlines screamed freedom:

“The hateful dictatorship has fallen!”

“Long live free Romania!”

“A new heart beats in Romania’s chest!”

Who wrote them? It no longer mattered. What mattered was that they were true.

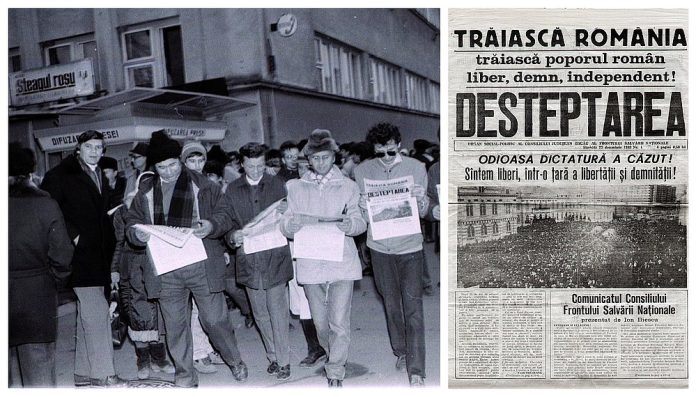

That night, 85,000 copies were printed. Before dawn, Mihai Buznea, Eugen Verman, Ștefan Olteanu, Petru Done and Ioan Enache carried armfuls of newspapers to the County Council of the National Salvation Front. Others distributed them throughout the city. Speeches were still being made from balconies. No one slept.

At 6:30 a.m., Eugen Verman’s article was read aloud into a microphone, in front of the crowd.

On the morning of 23 December 1989, Deșteptarea entered the world.

And with it, another Romania.